Art: Giselle Zatonyl

Text: DeForrest Brown Jr.

There is a cancer in the ecosystem that is the music narrative: genre populism. If the art is sick and the artist is weak, fending off the virus, then the curator, the presenter, the elaborator as Boric Gross wrote in Art Power is the cure, the hopeful panacea.

When we speak of music, we are left with a series of options and conditions, which had never been the case before. Firstly, we must ask ourselves if the very thing we're listening to could even be fundamentally called "music." Music, at its base, could be defined as the accrual and arrangement of sounds across a thread of time.

It has only been approximately a hundred years since the event of the famous riot (and riotous laughter) that erupted at the debut of Stravinsky's Rites of Spring. Adorno just as famously claimed that the piece was not music - too disorderly, too kinetic and (non)arriving - to arouse the senses of it's audience. And yet, what was not considered by Adorno and the riotous audience was that Stravinsky had hardly done anything out of the ordinary. If anything, he had played strictly by the rules; only, he stitched together several at once. Though he has denied the influence of Russian folk, the skeleton of the vacant and passages were definitely present amongst a myriad of other joints.

Adorno, despite this folly, did make more valuable claims in regards to the ontology of music. In his book the Culture Industry, Adorno did declare that “Voices are holy properties like a national trademark. As if the voices wanted to revenge themselves for this, they begin to lose the sensuous magic in whose name they are merchandised.” This was an extremely interesting, and obviously still controversial claim. What Adorno spoke to when he "called out" the voice was it's virtuality. The voice was a point of entry that had essentially become an end. The voice for listeners took precedence over the music happenings of a piece, reducing the capabilities of what music could accomplish.

In modern music writing and experiencing, the voice is just one of several cancerous monoliths that exist. Unlike the early 20th century where industry was still burgeoning and media was a slither of a dream, today we are completely enveloped in the virtual. The reality of today's society is that it is frantically pulled into the virtual and spat back into real at an alarming pace due to our consistent engagement with prepared social media, constant contact, and so on. Rather than wield the media, the media has, like a kudzu plant, overgrown and entrapped us.

Music, always dealing with the sounds available, took no time in engaging with these modern conditions. Through endless deconstruction, musicians have pushed music outward, dealing less with sound as material and more with our engagement with those sounds: an attempt at a conceptual 'copernican turn'.

To turn is to shift or move from a central point, and music's central point, always an assumed axiom, was that music was for us. The essay states quite clearly the boundaries of between pop and non-pop, separating what people consider to be music "for consumption" and music that is "for 'serious thinking'", i.e. music that is not for public ears, but to be stored away and regulated to staunch music aficionados and those who pretend to be "difficult", i.e. those who have been defined "hipster." Though, I agree with the distinctions made, I still find it very disturbing that writers are willing to engage with this type of formality of music bound to a consumptive end.

If one can have music, then it follows that all music is potentially theirs to have. This is mistaken. Anthropocentrism was meant to give meaning to the act of human's human-centered understanding of the world. There is nothing had or created about music, music is quite strictly the manipulation and transformation of available sounds. In modern cases this has been extended to the context and histories surrounding formalized patterns, definable harmonic constructions, the number of beats per measurement of time, etc -- but never applied to the formalized patterns themselves.

When people speak of music genres they speak in terms of brands and exchange value, and ultimately in terms of some virtual correlate What this means, is that music is taken for its ultimate surface content as opposed to the systems that build it up, which has lead to a complete standstill in music writing and thinking.

Music writing in its current incarnation exists in two distinct spaces: that of the lifestyle blog and that of hampered aesthetics theory. The first is an easy to define situation. When something is not understood, it is consumed and hushed. And moreover, like stated earlier in the essay, music is assumed to be apart of our lifestyles and not our environment; so, it is removed and trivialized by recordings and mulling over the actions of the musicians. The second instance is a little heavier, and is unequivocally tied to the first instance. Music being something that can be bought and had gives way to the thought that it is something that can be thought of in terms of the interests of its owner. Basically, if one is interested in music as say, propaganda, that is music's purpose for that person.Regardless of the interests of the owner, a music's phenomenal shape and timing matters much more. Why open a box if you are more than willing to tell the box what it contains? This has been the entirety of music writing and thinking.

Returning to Rite of Spring, the riot ensued because the terms of the piece was not clearly stated. Stravinsky did not tell the audience what the piece was "about." There was no about-ness, there was only the systems at play. Music exists only to display how flexible and malleable sound can be, as it is made up of frequencies and the movement/development of those frequencies, not of love or sadness or political agendas. But despite this, music writing and thinking tramples over the obviousness of resonant tones and shifting time signatures to say, "this is what I feel." Music makes you feel what it wants you to feel, on its terms.

But this is not meant to speak to the subjectivity, instead it is meant to speak to the virtuality that subjective experience anthropomorphically creates. What then is the state of music when music becomes able to mimic the subjective and signifier-oriented ontology which humans have created?

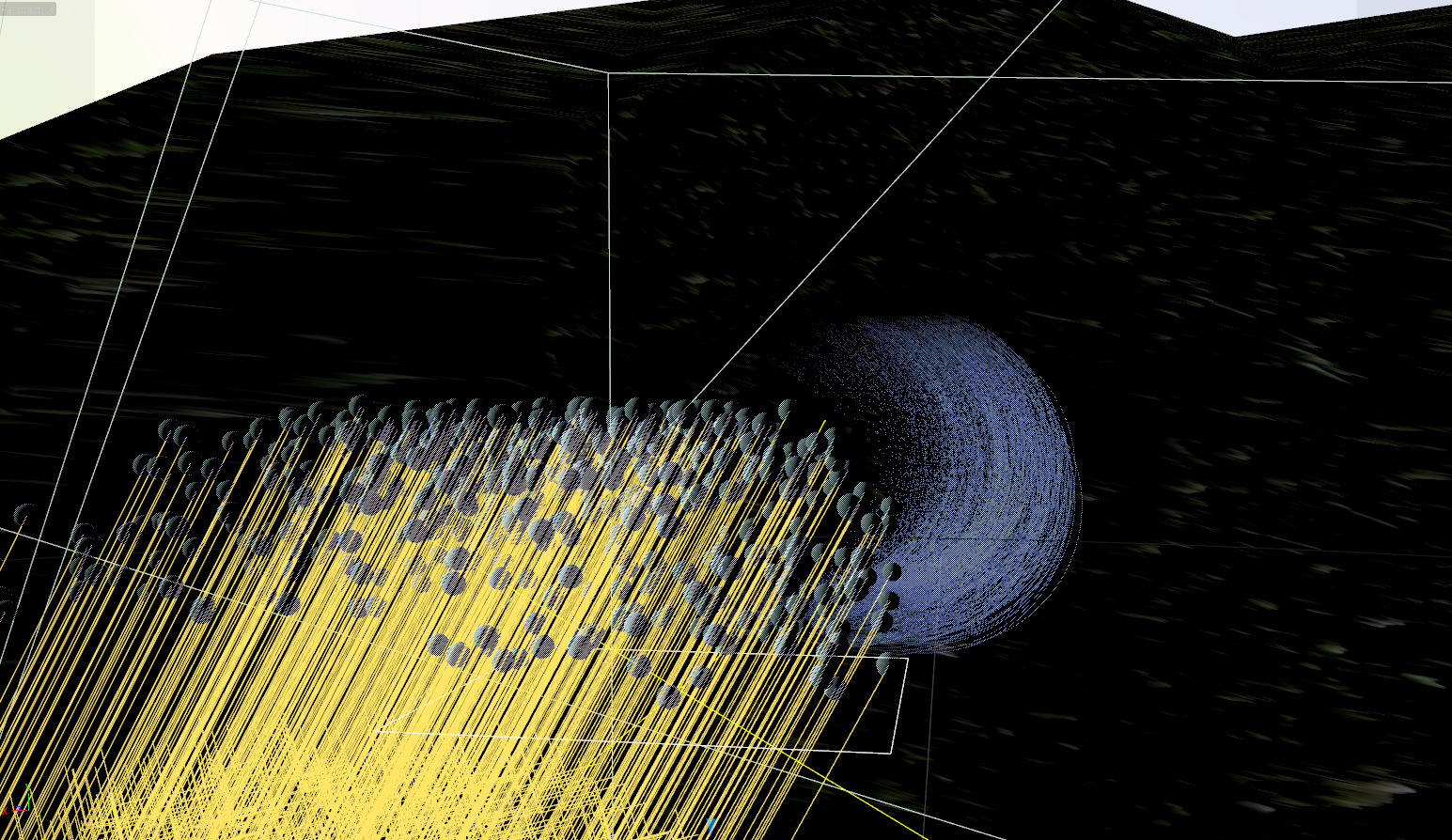

Theorist & multi-media artist Giselle Zatonyl explores power structures within digital-networks & systems of generative consumption. Her work presents pathways to re-approach community building & question the inevitability of corporate-state infrastructures.

DeForrest Brown Jr. is an essayist and critic. His work has appeared in The Quietus, Rhizome, Avant among others and is a regular contributor to Tiny Mix Tapes.