(1) Good Muslim Boy, 2013. C-type print, 155cm x 330cm

Abdul Abdullah was born in Perth, Western Australia in 1986, and he graduated in 2008 from Curtin University. In 2009 Abdul received the Highly Commended in the NYSPP at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra and was named a Perth Rising Star by Insite Magazine. His work is included in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, the University of Western Australia, Murdoch University, The Islamic Museum of Australia and The Bendigo Art Gallery. Most recently his painting 'I wanted to paint him as a mountain' of Richard Bell was selected as a finalist in the 2014 Archibald Prize. Abdul is represented by Fehily Contemporary in Melbourne, Australia.

N|A: This summer, you have your first American show coming at the Chasm Gallery here in Bushwick. Tell us about the work you'll be presenting.

Abdul Abdullah: I haven't made it yet. I should have more information, but it's going to be at the end of July, beginning of August. Based around similar things that I've been working with before but for a new audience.

N|A: Your work deals so specifically with politics in Australia, is this show going to attempt to deal with American race conflict directly?

AA: A little bit. I had a show in London and the series the Siege that I made for London, was a bit more international than my previous Australian show. And I think I'll continue with that with the American one, give it more international access points.

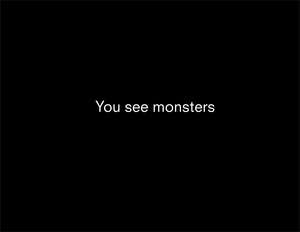

N|A: That makes sense. There's so much in your work, that I can see myself getting ahead of myself. What I really wanted to focus on, talking about Siege and maybe use that as a jumping off point for where you're going and the things that you're using, to connect to that work, explicitly. I've got random notes here, so I'm trying to make sense of them as I'm asking them. For me, there's the image, there's the text as it is the title, and then there's obviously the poem. And all three form the body of the work, but each component sort of functions differently for me. So I wanted to start with just the image. Where did that originate for you, the idea of it?

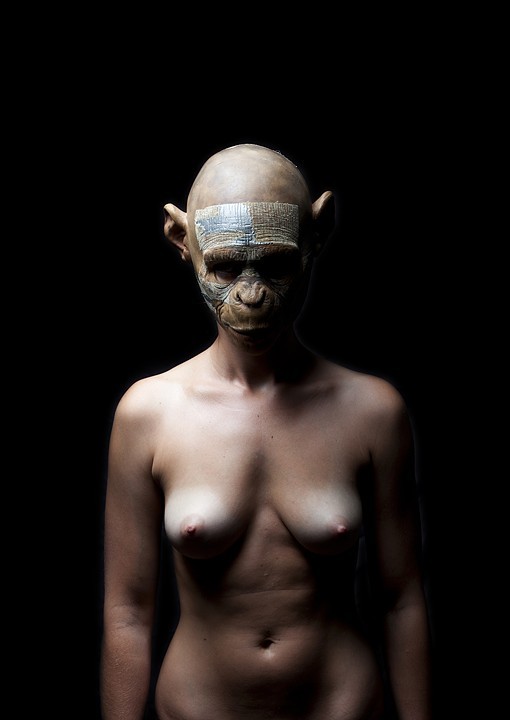

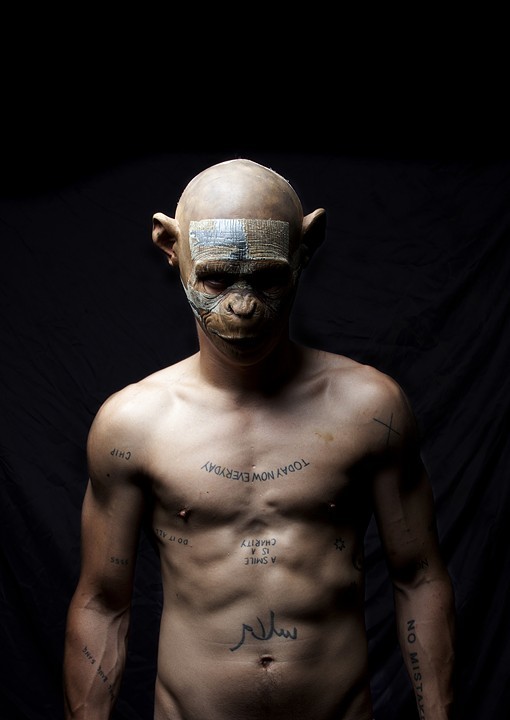

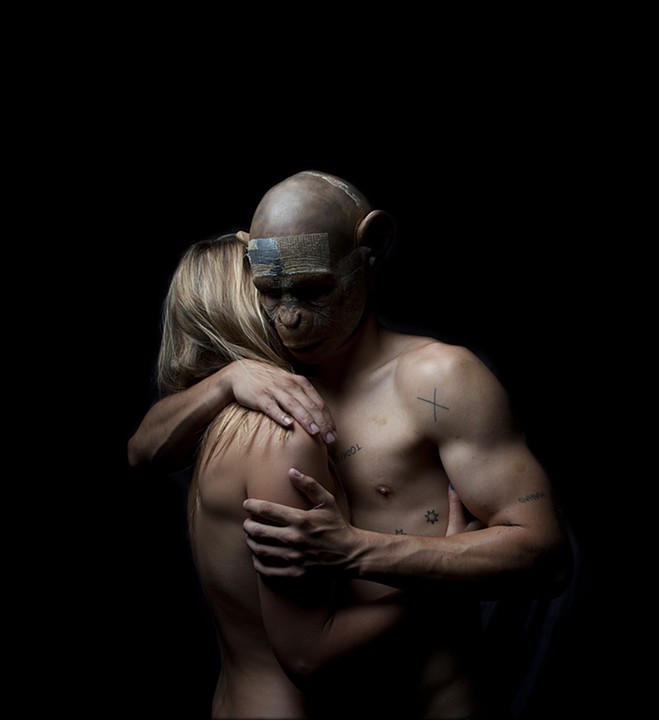

AA: How it started, I'd been thinking about all these different things. The idea of global colonization, and its effects, the byproducts of that, reading things like Franz Fanon and all these things influence my practice, books and that sort of thing. In regards to the imagery, what started it off was quite a fortuitous meeting of two different images where I was sitting there watching the original "Planet of the Apes" on my laptop, and on the TV in the background it was old footage of the first Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. It was images of the Mujahedeen, who are now the Taliban, I guess, riding along on these horses with Kalashnikovs across their backs. And on my laptop there were these images of gorillas or apes with these Kalashnikovs across their backs, riding along on these horses chasing down the humans. And there was a really direct link; I couldn't help but feel that this depiction of the other was a correlation that I couldn't ignore.

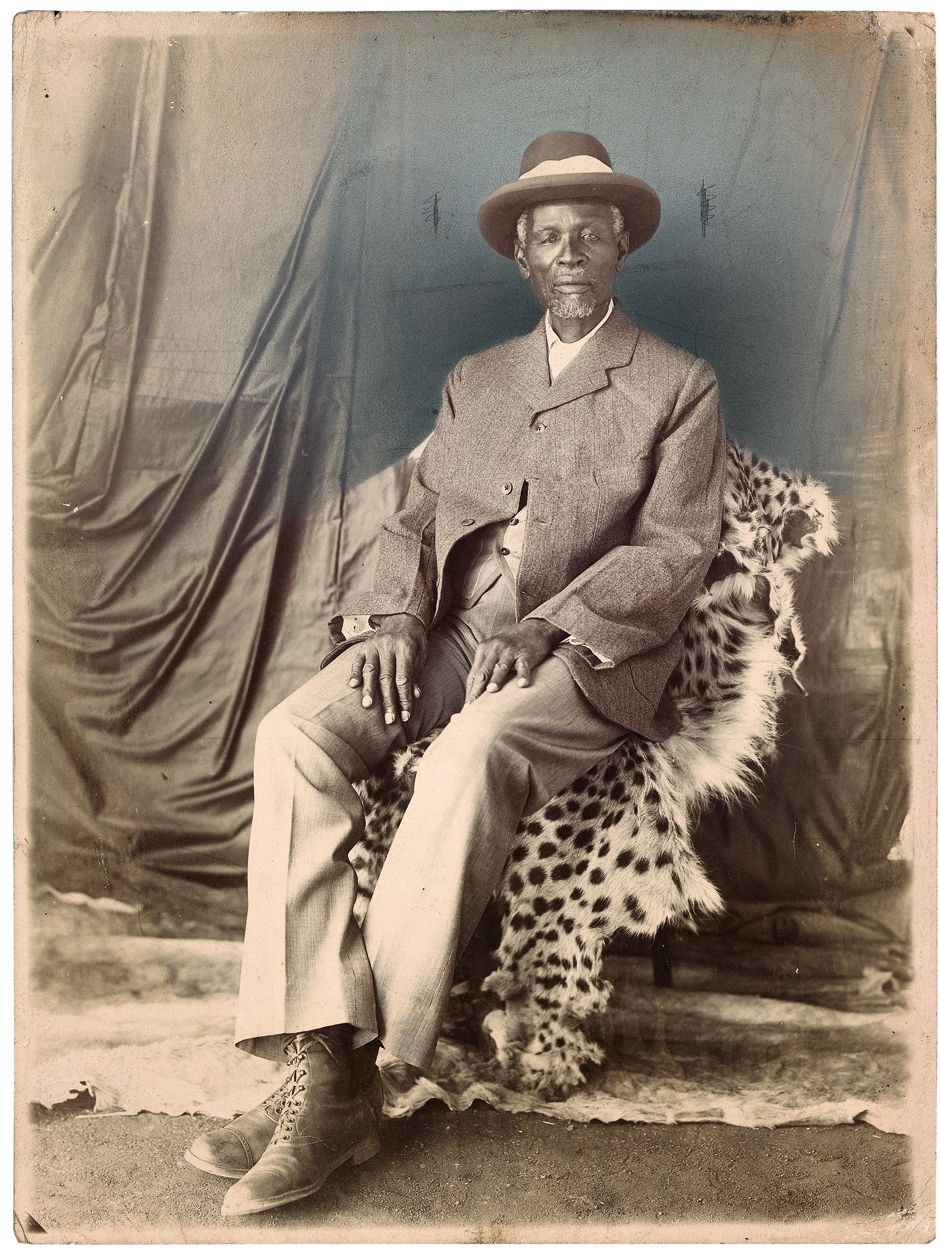

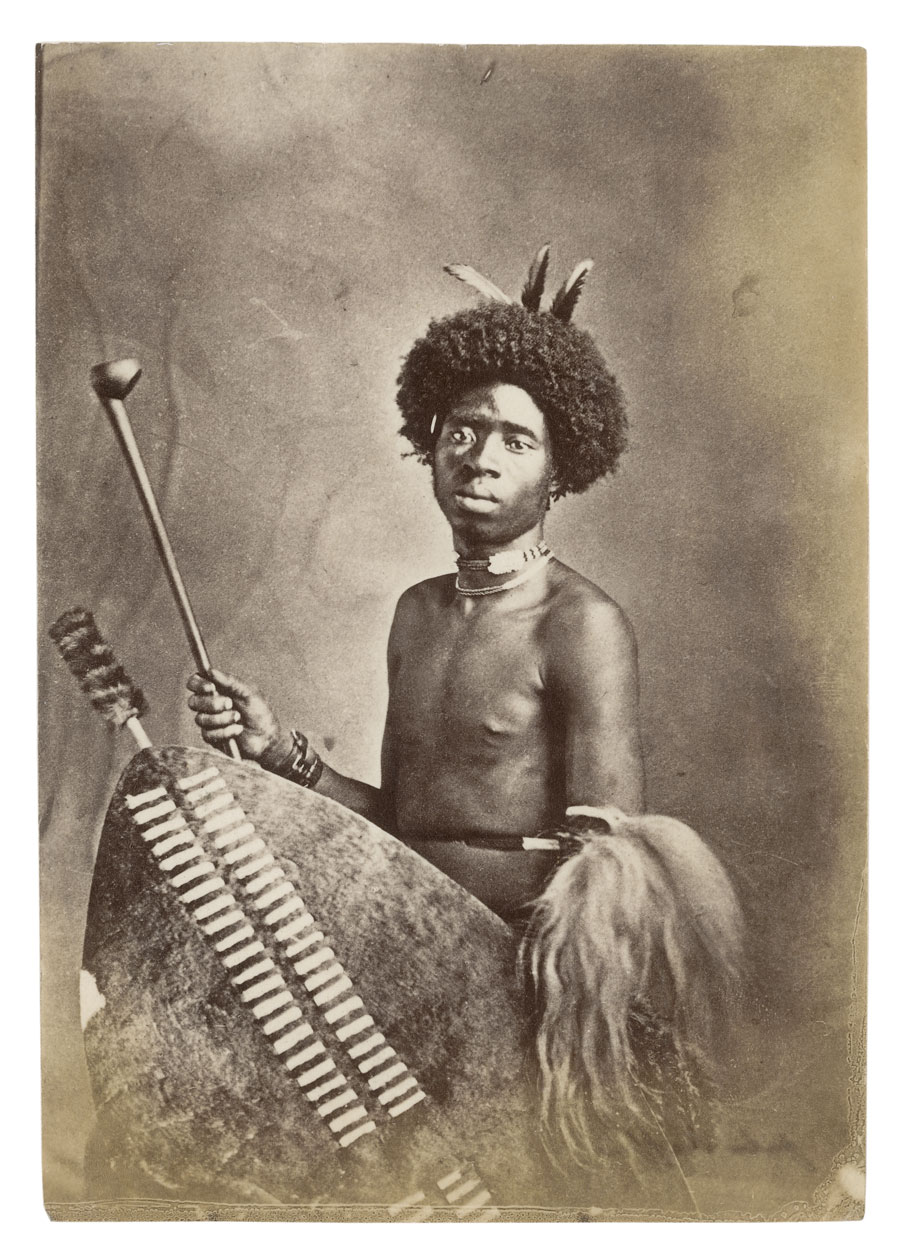

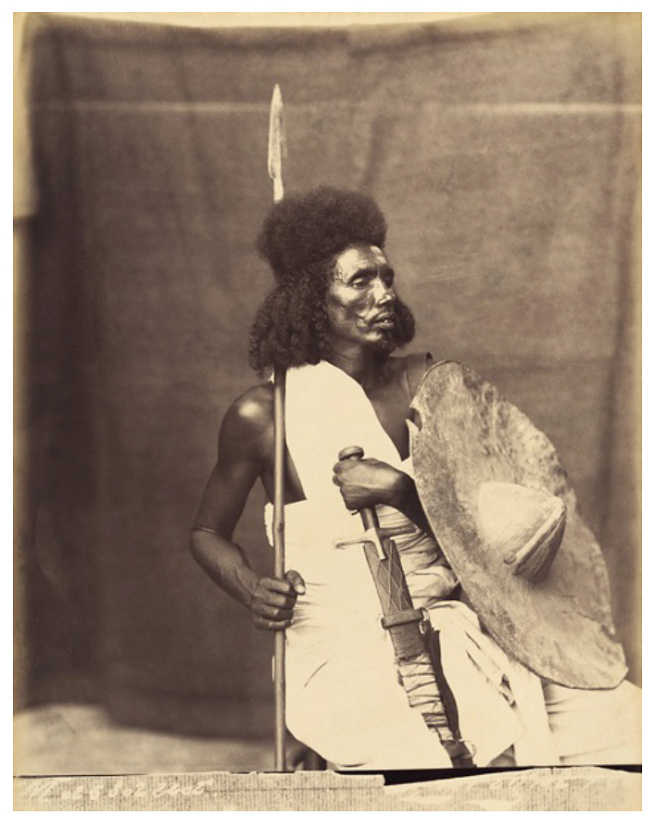

(2) Seige, 2014. Ten type-C photographic prints

N|A: Really interesting. In the newest of the new "Planet of the Apes" that came out last summer, in a lot of ways they made that link far more directly to Native Americans and white American settlers. Some of the images of the apes on horses were straight out of a western. The whole narrative of the humans in their little bunkers, was totally like the settler narrative from westerns. It's an inescapable thing. It's funny, I think the original "Planet of the Apes" creators of that film thought of it as somewhat progressive. So it's kind of interesting, I wonder what they really felt about the complex imagery that they were presenting as time went on, or if it even occurred to them?

AA: It's interesting what you say. The depth of the political narrative in those original movies is really surprising by contemporary standards.

N|A: Did you ever hear the stories of the making of that film? The actors, when they went to lunch, no matter what their star status was, they would go and eat in their groups of ape costumes. Like all the gorillas wanted to bond together, and the orangutans with orangutans. There was like something deep inside of them, "That's my tribe," and it transcended their status as actors. Humans are weird. What about the framing of the image itself, when you came down to actually producing them? Obviously you could paint that, so what was the decision to do that with photography?

AA: I found photography a really useful medium, in that it comes with its assumption of evidence, maybe an assumption of proof, a bias of proof. By that I mean, a painting is from someone's head, it can be complete fantasy, while photography seems to capture something that's real, even though you can mess with it just as much as a painting with Photoshop, do whatever you like with it. I mess around with my photos quite a bit, but it keys into something like a memory as opposed to a fantasy. Does that make any sense at all?

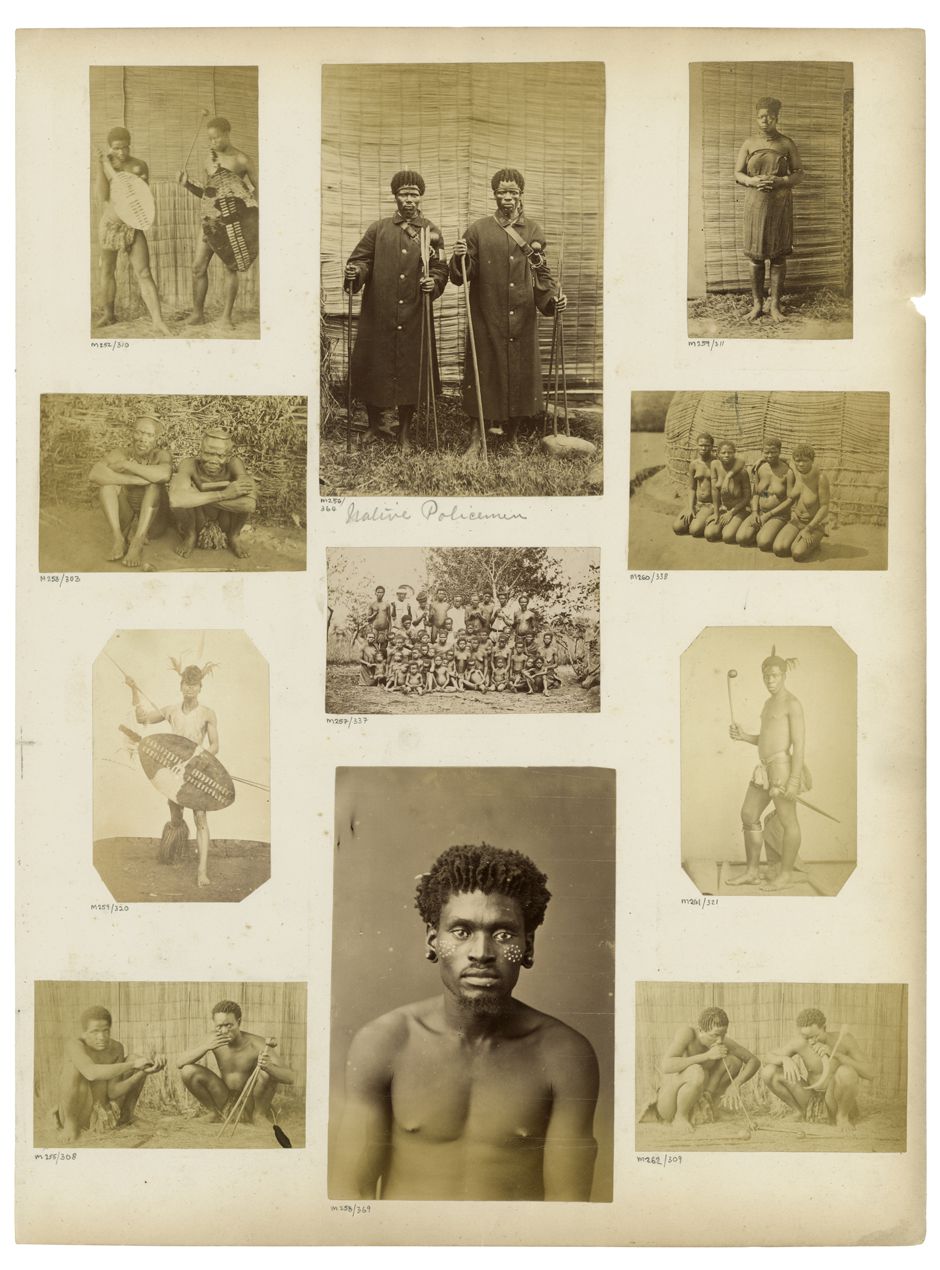

N|A: Totally. Obviously, even the image that you have, the painting that you have that is a very similar sort of ape face, it's not as confrontational. It just doesn't jump out at you in the same way, because it is this mixture of the real and the abstract. To me these photographic images are connected to early anthropological studies. I pulled this book off the shelf, which is African Photography from the Walter collection. Distances and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive. It's all these early photographs documenting Africans and you can really feel the European gaze. Here even that kind of framing...

AA: You can see a direct link there, totally

(3) Various archival images held by the Walther Collection.

N|A: So that kind of jumped out at me, especially the ones where they have the photographer making a point of focusing on traditional dress. It's similar as well to Edward Curtis who documented native Americans and a lot of similar 19th century ethnographic studies. I'm sure there must be equivalent images of Aborigines in Australia. Was this a reference point for you?

AA: I can't claim that it was specifically, but I think it is inherent in the work. I must have come across work like that, images like that before. Because I can see exactly the link. I didn't have it in mind when I was doing the work, but it has to have been an influence.

N|A: It's also like the Natural History museum tableau, that same kind of dramatic lighting.

AA: Yeah, I really wanted to have that theater, that drama.

N|A: Which definitely comes across. How do you go about staging them? They're so well done. What's your background?

AA: I work with a particular photographer, and we've known each other since art school. Actually I'm at his house at the moment. David Collins. He's a magnificent photographer. We have a really good shorthand with each other, and he really understands the type of processes, the lighting effects that I want to produce. When making it theatrical like that, I don't want to present a documentation of something that happened, but really make it clear that it is a bit of theater as well.

N|A: That leads me to what is striking on the images, first is, I don't know if you've been following the Ferguson Missouri, and Eric Garner and Tamir Rice that's going on in the States.

AA: There's not as much on the news in Australia, but online, I've been watching it.

N|A: With Ferguson, Darren Wilson, the cop, in his testimony to the grand jury, the way he described it, was that Michael Brown "looked like a demon" coming at him. And what the jury finds then is, well, he “reasonably feared for his life.” But the whole premise of what his reason is has to be considered unreasonable, because it's founded on that kind of racist iconographic imagery. So when you're confronted with the images, it's almost like a racist's nightmare. It could be straight out of the Nazi newspapers. So it's Siege, and who's under Siege. But it seems that it's like that white fear primarily, because you're in that position, you're putting me in the position of someone who's viewing in. How do you think about that relationship between the gaze?

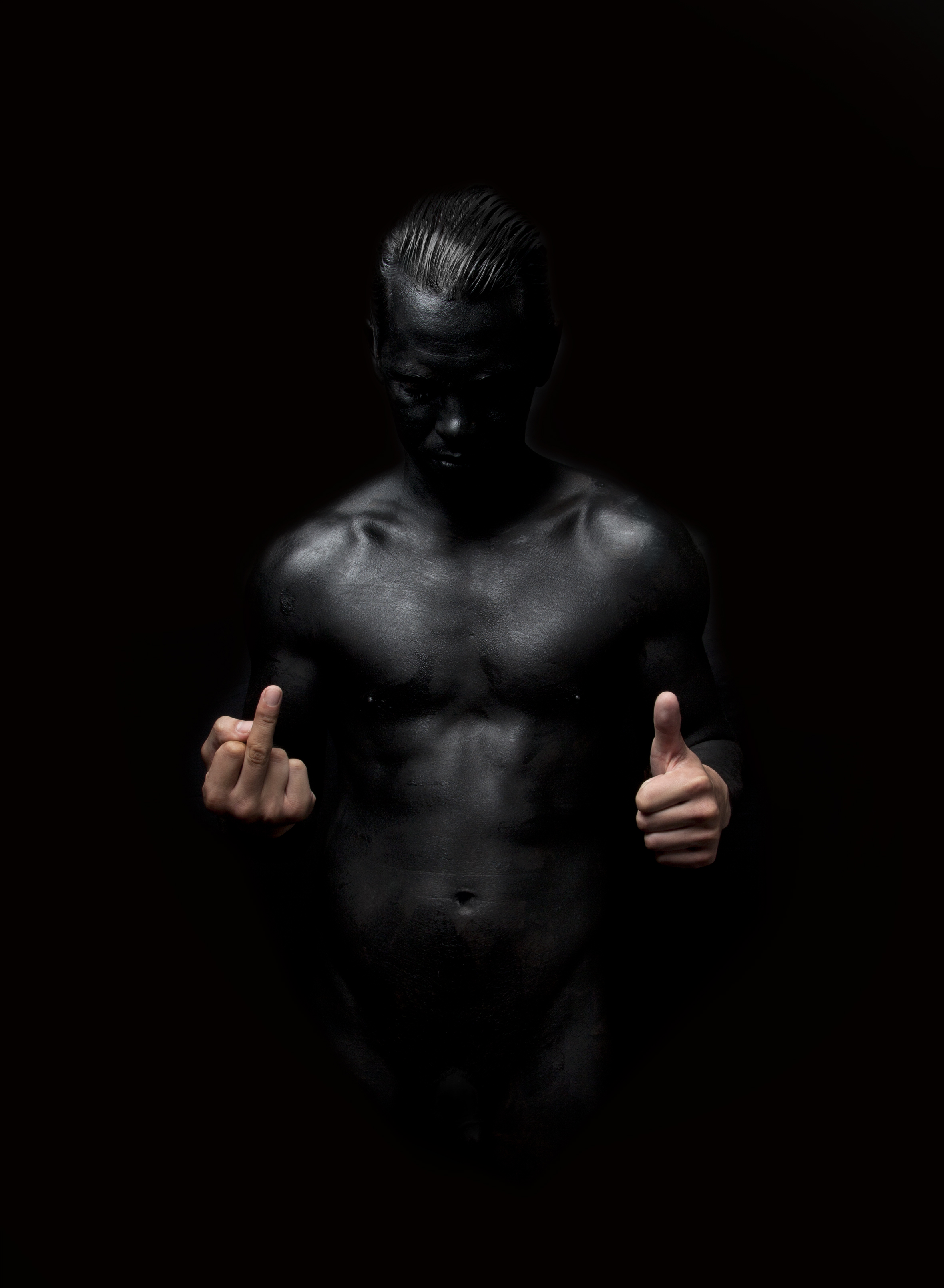

(4) Bugi man, 2014. Giclee print, 145cm x 110cm

(5) The Re-Introduction of Australian knighthood, 2014. Giclee print, 145cm x 110cm

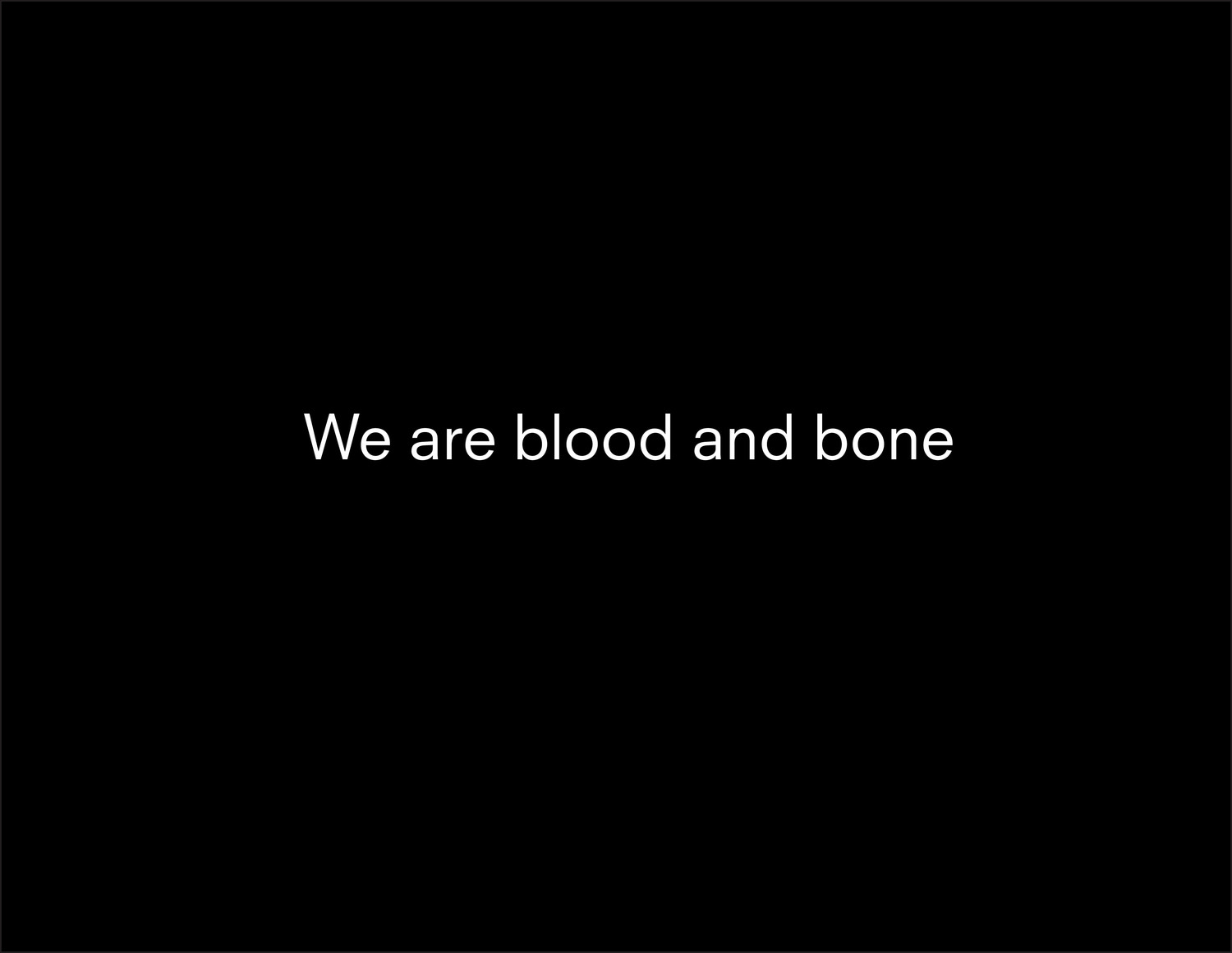

AA: I like the ambiguity of the title. My brother, who's also an artist, he hates ambiguity. But I really love it. I like a sort of flux in what I'm trying to put across. Siege is an example, talking about this colonized group as under siege, but also the audience is under siege by these works, by these large groups, and sort of playing around with our flux. And I'm not putting my foot solidly in either camp. Does that make sense?

N|A: I'd like to unpack that a little more, because obviously I know the work was kicked off as well with the London riots; you said you made it for London. So can you go into that in a little more detail, who these characters are, what that mentality of watching is?

AA: The characters that I'm portraying, one of the works about halfway through the series is called "A Disaffected Byproduct of the Colonies." And that pretty much sums up who these figures are, and what I'm trying to represent. The riots, an example like the civil unrest of the Arabs, the Arab uprisings; they sort of, appeal is the wrong word, but I am attracted to them in that they are these efforts by a frustrated mass of people that potentially don't have the access to means and ways of changing things, making things better for themselves. Like a last-ditch attempt. What really got me interested in them was the Cronulla riots in Sydney. I don't know if you've heard of those riots in Australia, but they happened in 2005. You can see it on YouTube, it was a race riot, like 2-3,000 white people marching up the beach attacking anyone who's brown, dark skinned. That happened while I was at art school, and that really stuck with me. I've been keeping a close eye on those things. I don't know if I skirted your question.

N|A: It's not really a direct question; obviously your work challenges everyone to think about these things. I was just thinking about it, how it worked. You've got the affectation of the mask; the clothing choices from the track suits to the religious garments. How does that work in the work?

AA: The track suit for me is the uniform of disaffected youth across the world. It's a signifier that I can latch onto and I think it's immediately effective, playing with contradictory signifiers. So getting a couple of signifiers in the one image and the tension that it creates, people can engage in that tension and can push people into different directions. The work in Siege is confrontational and has the potential to be quite insulting to people. I’ve had a lot of discussions within the Muslim community with people finding the work potentially offensive.

N|A: Which is that first point of confrontation that I’m talking about. It is a visualization of that racist image, I mean, horrifyingly. So there’s been an interesting conversation in the community itself. How’s that played out?

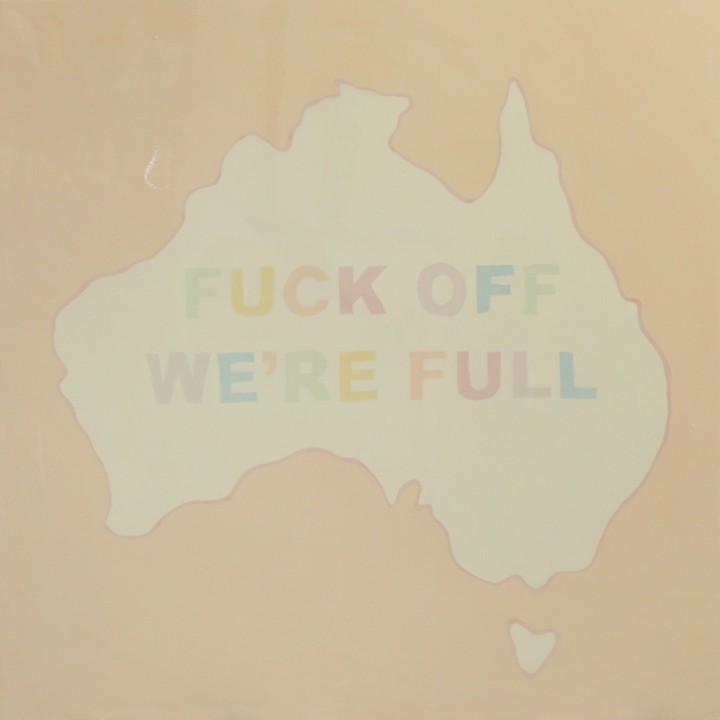

AA: It does take a conversation. If people were to see it out of context, it could go either way. But I like that risk, that danger, where if you didn’t have the context you might read it completely differently. In a way I think that’s more exposing, useful that saying “This is what its about.” I did a work in 2011 based on an Australian bumper sticker, and you’ve probably got them in the States as well. But it’s in the shape of Australia, and it just says, “Fuck off, we’re full” and you see it on the back of cars, and it’s a xenophobic thing. I find it quite offensive, maybe it’s talking about me, about my mother. And to engage that I turned it into a lightbox, I made it really big and made it glow in the dark so people couldn’t ignore it. But I also provided it without context. And at the opening this old guy came up to me, saying, “You’re right, we are full,” and that’s not at all what I was trying to put across. But I liked that that potential reading was there.

N|A: That’s what’s interesting to me in the images in a piece like that is that you’re bring that out in the conversation in the open, sort of forcing people to choose sides. And the title is what gives it its context and flips the title Siege into something else. It’s described on your site as being a poem. Was it written as that and then attached to the work, or written for the work?

AA: They sort of came together at the same time. There were a few statements, like “You see monsters,” the first one, “The Disaffected Byproduct of the Colonies” is another one that wasn’t necessarily going to be part of it, but then just sort of floated in. Those were the basis for sort of filling in in-between, and the images were married to those. I had the first titles and the brought them together.

N|A: How do you generally view these intersections between image and text in your work? It’s a common thing you’re playing with.

AA: I think it’s vital. The text or the title is as important as the work is. I came across a New York painter, I can’t think of his name, but he did these really beautiful paintings of the city, cityscapes, very quiet paintings, no figures in them, just these buildings. But the titles of the works were the headline of the day, which were quite graphic and full on. And with this peaceful image combined with a full on title—that stuck with me ever since, that these two things can work together so strongly to shape the context.

N|A: So it’s been something that you’ve always played with. What you’re working with is so text based, like conversations, directly linked in that way. And you give speaking tours. Do you find yourself as you become more well known as this political artist? Forcing you to talk about things more?

AA: I think I have a responsibility or at least an obligation to speak on behalf of the work. I could never be a spokesperson for anyone else, I’m clear stating that, I’m not going to speak on behalf of the Muslim or the non-Muslim communities. My work is coming from me based on personal experiences mostly. I find it useful to speak about it, it’s interesting to have these conversations with people that I might not have. I find it kind of funny that people want to hear what I have to say.

N|A: Your work, especially this series, is really present, really dealing with things that have come from your context and things that are going on now. Are you looking at historical representations, like those pictures of, the historical ideas of marginalized people and race and identity?

AA: More and more so. When I was first engaging in political ideas in 2011, something I was always interested in doing but really started feeling more confident with it more recently. At first I was looking at the Australian experience, but now I’ve been reading more and getting a broader understanding of the historical context of it all, understanding the history of colonization, the history of the other all across the world, but looking more at people like Edward Said and Franz Fanon, and the autobiography of Malcolm X, these pivotal historical figures and their discussions, these are becoming more and more of an influence.

N|A: Are there contemporary writers of similar stature that you’re reading? I’m thinking of something like “Fanaticism: on the uses of an idea” by Alberto Toscano?

AA: I guess the focus is really on writers of a few decades ago. I’m catching up.

N|A: I had a question about the marginalization. Every one of the images is the lone figure. I was wondering how that related; was that an accident, or is that something conscious?

AA: There a couple of shots with a man and a woman.

N|A: Right, the one, the woman is turned away from the camera.

AA: It’s not an accident, but there’s no specific contextual or perceptual reason why I’ve done individual shots like that, other than compositional. When I’m constructing it the way I want to construct it, to have a particular focus point, I want to limit the signifiers that are in there. Contain them in the one body.

N|A: It makes them so powerful as a unit, because of the individual units comprising the larger 10-piece poem.

AA: It’s seeking to control the audience’s gaze.

N|A: The whole work, that’s what it’s really about, controlling gazes and what it means to control gaze and who has agency in that regard. So what is the work you’re shooting today?

AA: This is a little broader, using the motif of the bad guy but not looking at any marginalized or ethnic group, religious group, but using a balaclava. The main image that I’m working on is a bride on a beach, with a white wedding dress with a white bouquet, but also a white balaclava. It came from a comment I heard recently on the news, in regard to what was happening in Gaza, someone talking about terrorist babies, that their choice has been removed. It led me to the idea of a terrorist mother and father, with a terrorist child. So it’s my roundabout way of getting to an image that I quite like. I’m still working out the nuts and bolts.

N|A: How long does it take to construct a piece like this? What is the process? Does it begin with drawings, sketches?

AA: It begins in my diary, I scribble away and draw things and write a lot of notes. Once I’m happy with the composition and the elements that are going to be in it, I sort the material. And coming from Perth, which I think is the most isolated capital city in the world, there’s not much going on here. So a lot of my sources are from overseas, I get it online, then join together with my photographer David Collins, and we produce the work.

N|A: And you hire actors?

AA: I’ve got an actor here at the moment who’s going to help me, she’s going to be in the bride image, but the male figure is usually always me.

N|A: Is that a practical choice or is that part of the composition?

AA: You could say it’s a bit of both. It is for me part of the conversation in that I feel that to maintain that sense of integrity I need to be in the work. The risk of the work needs to be shouldered by me as opposed to an actor. There is a lot of criticism of it, and I’m very wary of the idea of exploitation, and I figure that if I’m in the work and it’s me that’s presenting myself, then I’m only exploiting myself.

N|A: Does that become trickier when you talk about going to England or America and sort of adopting things that are more international?

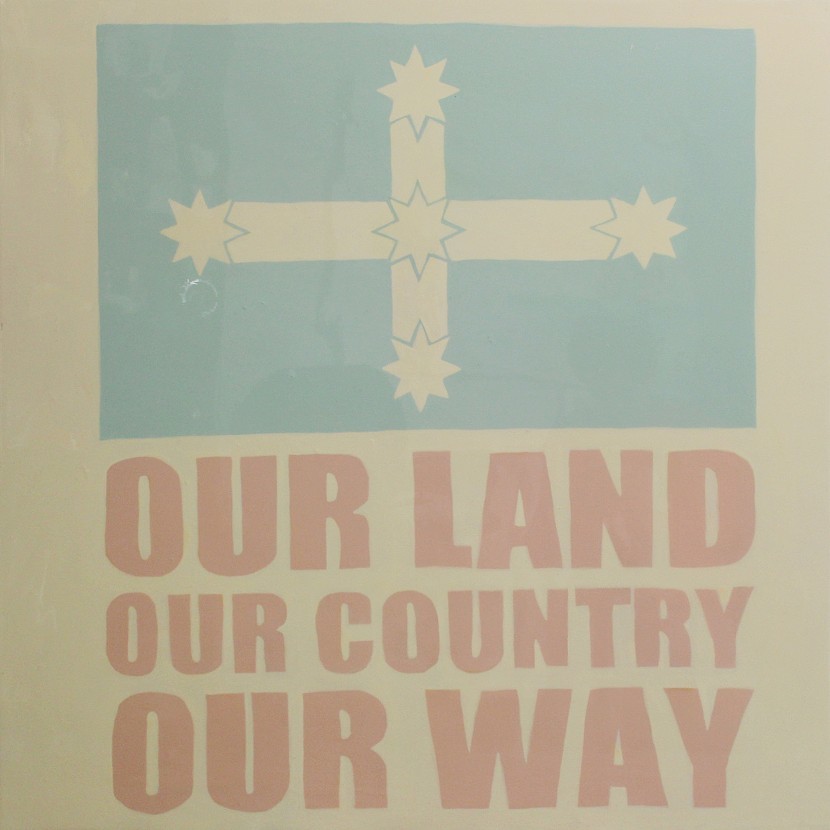

AA: I think it is. I was looking at the London riots, and for me none of the images were specifically English. When I go international, I have to be careful of the signifiers that I use. Like the Australian flag or the Southern Cross or images that I’ve used before, they aren’t accessible to a foreign audience. So I have to open things up a bit.

N|A: You said you haven’t done any of the work for the New York show yet. But have you begun research for that work; is it going to be photography based?

AA: It will be entirely photography. And I’ve begun researching. It’ll be on the same sort of themes. This bridal work might be part of that series. It’s all up in the air at the moment. With this American show it’s not like I’m softening what I do. Like someone told me before, that what I want to do is punch people in the face beautifully. Like slapping someone with a velvet glove. At the moment what I’m trying to do is work out what I’m trying to say, but maybe make the glove a little more velvet-like.

N|A: With the Ferguson thing going on and the protests now in New York for that, and the recent six year study on American torture that finally came out detailing the numerous ways Americans tortured people. These things, Ferguson and the war on terror are so directly linked, because it was essentially 9/11 that has allowed the U.S. police to become so heavily militarized.

AA: It amazes me how much military equipment American police seem to have, the images I see online, tanks. It’s crazy.

N|A: It all came directly from 9/11 and these police forces in the middle of the country getting money for that stuff to defend us from terrorism. It’s so heavily related that I kind of wondered, especially since your work deals with riots, about whether that’s where you’d be looking.

AA: I’ll definitely be looking at these sorts of things but I don’t want to reference them too specifically. I want to tread very carefully about what images and signifiers represent. I’m also worried about getting into the country. Or getting out of the country.

N|A: One thing that you said, track-suits are the international costume. I think it’s maybe not as much true in America.

AA: I suppose, yeah, that it’s a different theme. I’m imagining like a young French Algerian or someone in London. In America I guess it’s quite different.

(6) We Watch, 2014. Giclee print, 150cm x 140cm

(7) It Doesn't Matter How I Feel, 2013. C type print, 155cm x 110cm

N|A: Yeah, it’s a different kind of uniform. It’s interesting that there’s that link globally. Americans are just in their own heads. It’s interesting that it jumps to Australia and not to America. There’s no question there. But maybe it’s because America doesn’t think of itself as a former colony but mire something exceptional willed into being. Which is of course a very convenient narrative if you’re looking to gloss over little details like subjugation and genocide of native populations. And as Americans we still can’t talk about it, we don’t have any way of truly dealing with that history.

AA: There’s definite room for reflection in Australia about our treatment of the Aboriginal people. It’s appalling and ignored, but the massacres that happened here, everyone here is sort of implicit in that invasion or occupation.

N|A: In America you’ve got that and also the history of slavery. Now the current climate that you get when race comes up, like with Ferguson, is that you have the newscasters saying that people who talk about race are the racists. It’s very circular logic, but that’s how it is. We’ve spoken about the reaction of the Muslim community, what is the general reaction to your work in Australia?

AA: Generally it’s been pretty good. The people that I’ve come across react quite positively to it and see where I’m coming from. Very rarely is the criticism of my work based upon the work itself or based on the technical aspects of the work or what it looks like, or even conceptually what I’m trying to put across.

N|A: You’ve won these or you’ve competed for these prizes, that obviously brings you to an audience that’s beyond what you might find in an art crowd. That’s putting you on the front line of something. Is there a lot of heavily political art going on in Australia?

AA: There is a bit. But it’s primarily coming from contemporary Aboriginal artists like Richard Bell or Tracey Moffat. Their work is at the front line. To me that’s the most interesting work in Australia right now. The most negative things that I get in my emails are based on my name and my religion and their assumptions about my religion. So all of the hate mail that I get doesn’t have so much to do with my art as with my name.

N|A: Really?

AA: Yeah, it’s a strange one. I’m sure there have been people who’ve disliked the work for conceptual reasons. But the ones who write to me are the ones who think I just shouldn’t be in the country.

N|A: Do you get a lot of that?

AA: Not in the last year. There’s a prize called the Archibald Prize in Australia, it’s the most popular exhibition they have in the country. The first time I was a finalist in that I painted a guy called Waleed Ally, who’s a political commentator in Australia but is also a Muslim voice, he doesn’t like using the word Moderate, but he’s really a smart guy, not full-on at all. But there’s a segment in Australian society that hates him. He’s on prime time and they just hate his guts. And then they saw that there was this painting of this guy the new and hated painted by some unknown named Abdul Abdullah and it set some people wild.

N|A: That’s kind of remarkable.

(8)Fuck Off We're Full, 2013. Enamel and resin on board, 90cm x 90cm

(9) Our land our country our way, 2013. Enamel and resin on board, 90cm x 90cm

AA: Yeah, it was really weird. That exhibition toured regional areas, regional galleries on the East Coast of Australia. And there was a place called TarraWarra which is a really big gallery or museum, and the gallery sitter said when I visited the show that he hadn’t come across a more polarizing painting. It wasn’t like it was a crazy painting; it’s quite a safe portrait of a person just sitting there. But he said that people either liked it or just hated it. And the reason they hated it was the person who was painted and my name. Another thing about the Blake Prize, which is a religious prize. I won the Human Justice portion of it, and a guy called Khaled Sabsabi won the main prize, and the fact that two Muslims had taken up two prizes really shut people off. It really annoyed people; they wrote to the newspapers. Even politicians wrote about us.

N|A: Does that make you fearful?

AA: A little bit. But we don’t the same kind of gun culture; I’m not too worried.

N|A: Fair enough. That’s intense. I was listening to something today that was about how shockingly sexist our line culture is, which has been a very much belatedly emerging conversation. Basically just anytime a woman says anything, whether it’s political or not, the amount of abuse, and death threats, and graphic horrible statements are thrown at them. We’re told that the Internet is an inherently liberating concept that spreads communication, openness and all these things but really it’s at least equally a tool for spreading vitriol and using fear to control people. But aside from the fears in getting this kind of mail, is it frustrating that people aren’t engaging with the actual technical side of your work.

AA: No, not really. It sort of justifies what I do. When I first got some stuff I was really offended. But now I see that it’s just fuel for the fire. It proves its relevance to me and that I’m going in the right direction.

N|A: So this photography-based work you’re doing now—do you feel that you’re moving away from painting? Or is it just two sides of something?

AA: What I want to do is not be specifically just a painter or photographer—I just want to be an artist. I want the idea to be privileged over the medium. To use whatever medium. I want to figure out how a person can just walk into an idea as opposed to being presented it. And I want to move into room-sized installations, that’s my goal over the next couple of years, communicate my ideas by taking up the space.

(10) I Wanted To Paint Him As A Mountain, 2014. Oil on canvas, 180cm x 150cm