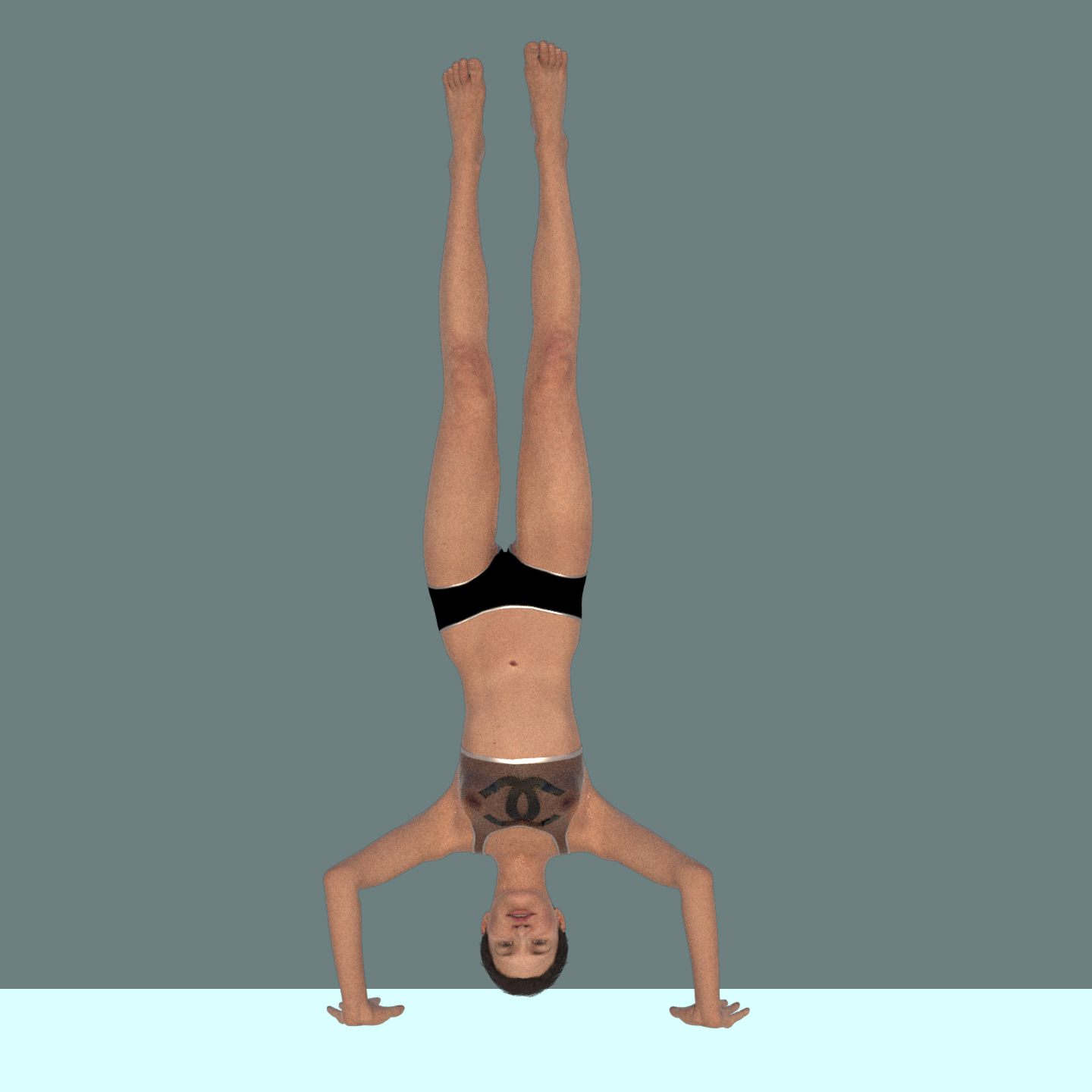

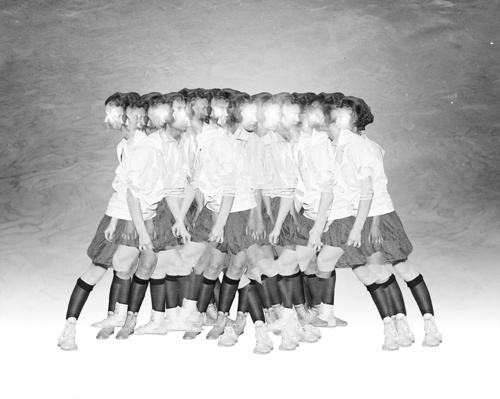

It is not by coincidence that the most popular of popular music began in America. Here, an unprecedented soup of people boiled together by the mechanisms of global capital created, as a byproduct, the most motley muddied mutt of culture: a world’s-best folk tradition that became Jazz, Honky-Tonk, Rock n' Roll, Hip-Hop, House etc.; the adapting voice of generations.

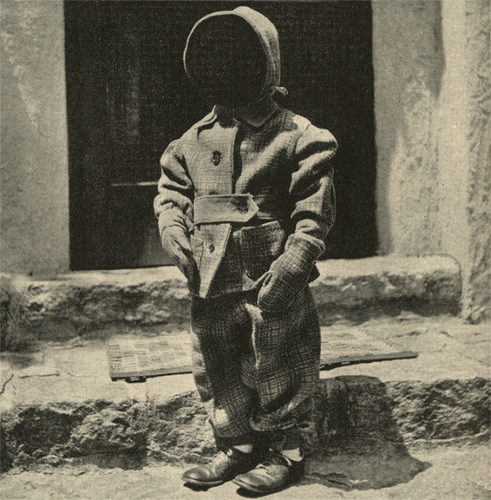

American music is a story of industrialization, of the creation of the modern world, and of how marginalized, otherwise voiceless people answered back. It is at every stage a story of futurism, of adapting to and away from new machines. Even the oldest variants—mountain music, ragtime, early blues—were not parochial and rural but mutating genes out on the frontiers of burgeoning urban landscapes where smokestacks blotted the sky and class, money and power—intrinsically fixed to the rising, inevitable tide of progress—collided. “Hard times on the killing floor” indeed.

Through mill-towns and factories, workers spread their cultures sharing and appropriating strands as they went.

1

America would give rise to a type of super folk music that music would return again to its sources at crucial moments—post-war Britain, post-colonial Africa, newly independent Jamaica—triggering new evolutions and directions.

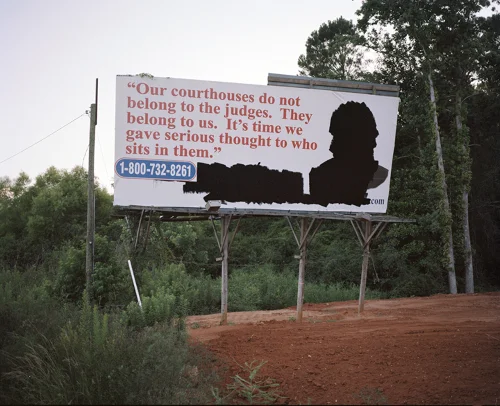

Political, social, religious, this music gave voice to disfranchised communities, "CNN for black America,"

2

bum-rushing the gates and barriers between race, gender, class and sexuality, even while its genres, trends and most popular (corporate) values became appropriated to re-strengthen the borders and solidify power structures. Folk music would follow the Great Migration of African Americans and the multi-ethnic working class through industrial America, spread on and evolve with almost every major culture defining technological advance of the 20th century, reflecting both the rise of capital, the collapse of urban centers and eventually their rebirth and gentrification.

At various points the very act of listening to it, tuning in to it, would in and of itself be a radical and political act, challenging notions of acceptability, establishing independent networks of mutual support and threatening the cultural hegemony. At times this threat would be aggressively and violently put down, spied on and manipulated. More often it would be co-opted, cleaned and made polite. In the end, as the 20th century drew to a close, folk music would become accepted, universal, ubiquitous, mimicked, looping endlessly back on itself in a state of permanent-presence.

3

Its power to unsettle, to be more than a decorative art, would become diluted just as its individual currency, devalued through hyper-inflation, created new value in ancillary feeds of user data. It is again, not an accident of history that at the same moment American cities began their renewal and gentrification—spear-headed by new theories of the creative class—folk music risked becoming ornamental; the voice for a new cultural-hegemony of flattened, cloud-based mashups.

Adaptation is always the key, an aesthetic survival mechanism that flourished through all these mutations, on all of these fronts and in this great multitude of circumstance and context, reacting both to and against market forces. Each mutation establishes a network, a clandestine means to challenge or usurp institutionalized control even when this challenge is only a subconscious action. The question we ask ourselves is whether this capacity now needs only one final shift

4

toward transhumanism.

5

Does the rise of digital networks, and what we hope will always and forever be open and thereby keep free the nodes of communication, make the need for subterranean networks irrelevant?

6

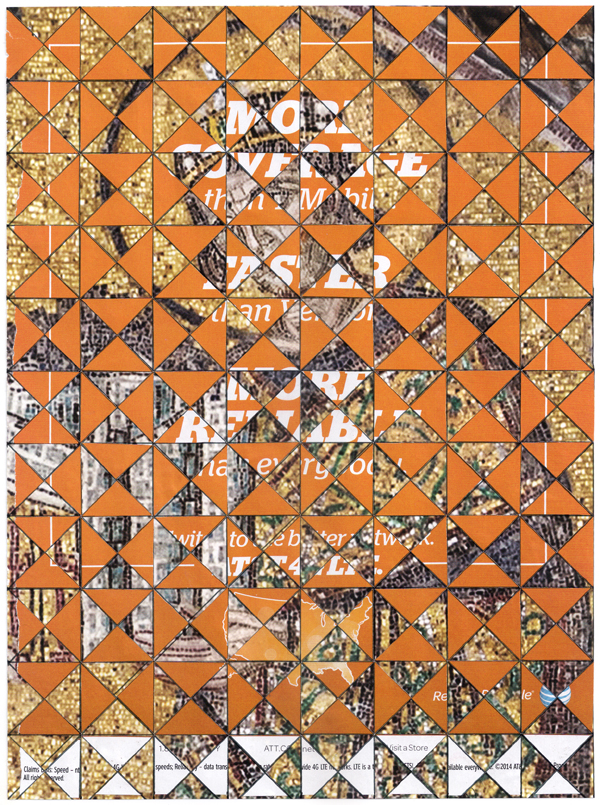

Technology is, it is said, on the side of accelerated copying

7

and the free-flow of information breaks down the traditional gates between cultural classes. We are repeatedly told of the inevitability, the manifest destiny, of technological progress and that to question any of it is tantamount to being against openess and human potential. But, what do we make of these facts when inequality seems to grow parallel to Moore’s Law? How do we make sense of agendas and rehetoric that so confusingly unites free-culture advocates, progressive scholars, venture capitalists, libertarian entrepreneurs and investors in a great showing of solidarity? This network to end all networks giving us both the tools to subvert corporate culture even as our actions facilitate expanding revenue streams to justify Wall Street’s faith.

8

Is it even possible, even relevant, to dream of a network not so much off the grid but running parallel to the homogenized global system of corporate value? Or have we come to a peaceful agreement with conglomerate multi-national corporations,

9

trusting them to manage the infrastructure of the network, to say nothing of their capacity to aggregate and organize our tastes? Is adaptation to the needs of the network, to feed the feed, our primary occupation?

10

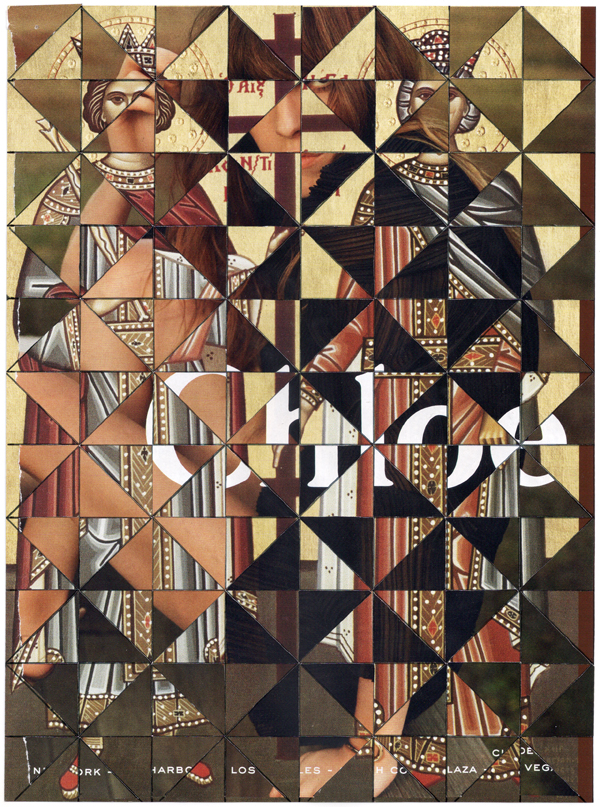

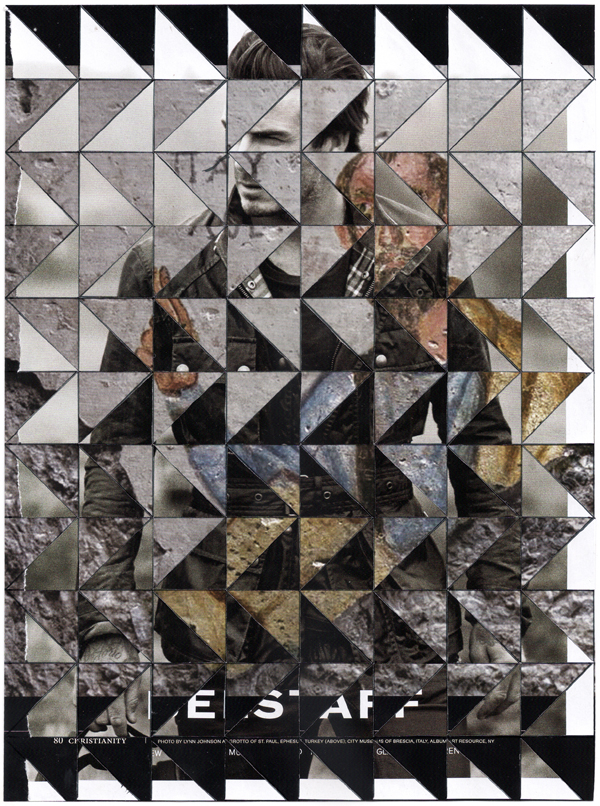

Were we all along wrong to worry about monopoly, monopsony and corporate control of our cultural legacy? Now that “advertising has saved indie music,” is it safe to abandon gates knowing we’ve made friends

11

with those we always perceived to be philistine hordes?

12

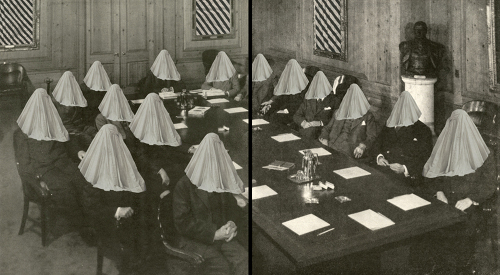

With so much attention paid to gates that preserve institutional hierarchy, are we forgetting the need for gates that protect vulnerable communities from those very institutions?

13

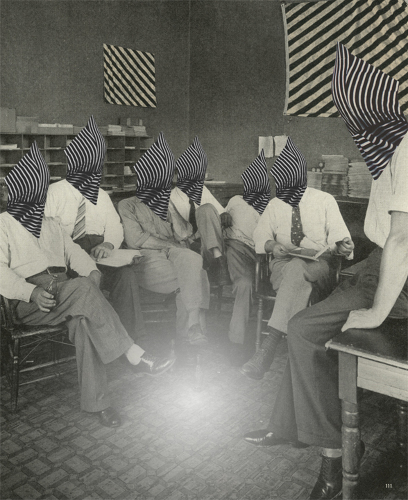

As our streams and connections are rearranged by algorithms designed with obfuscated ideologies,

14

freely manipulated with social-experimentation to alter mood

15

and the likelihood to vote,

16

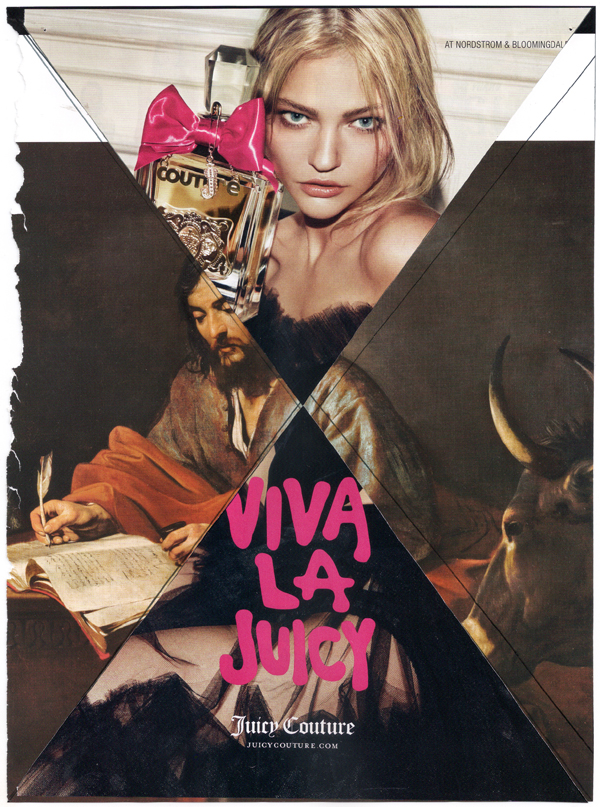

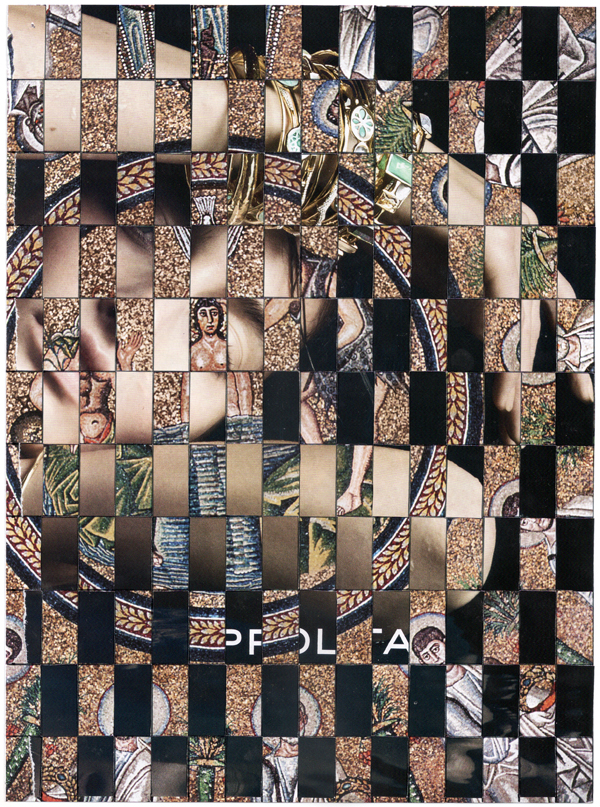

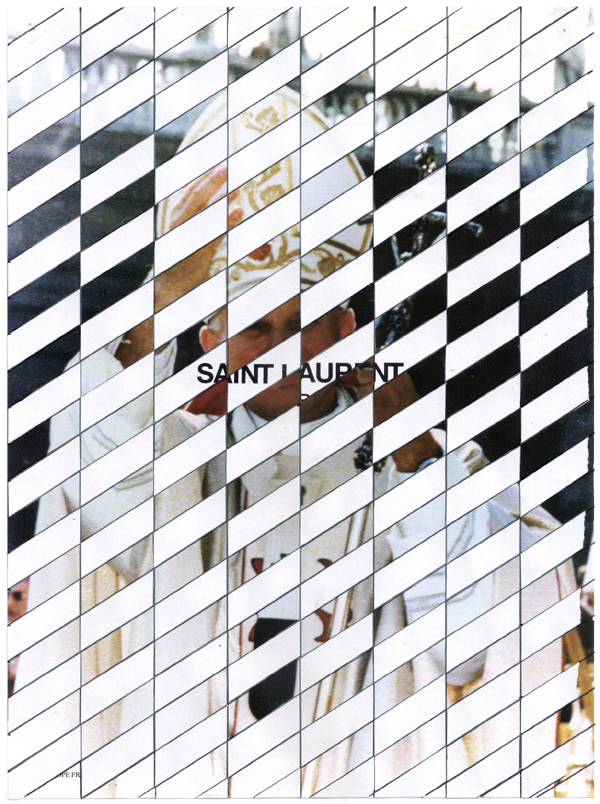

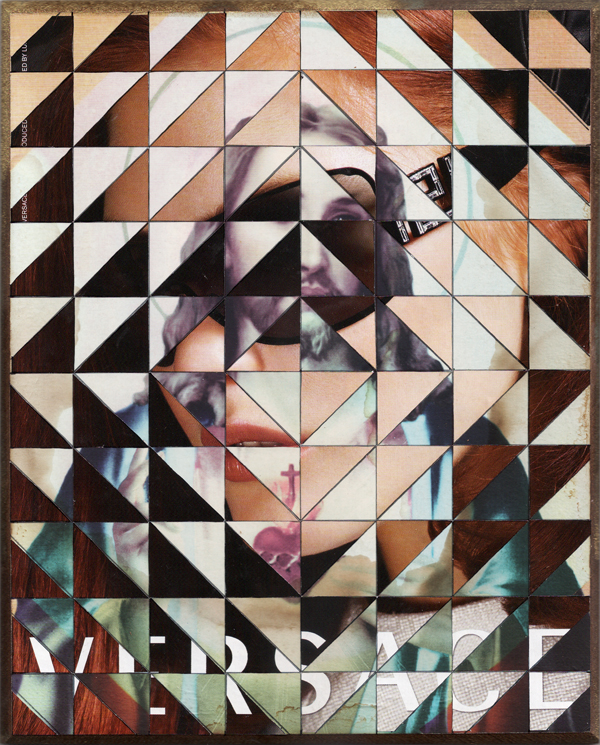

can we trust our voices are our own? Does any of this really matter when the right to consume un-impeded, without restraint and with the aspirations of “kings and popes”

17

is so utterly and wonderfully fulfilled?

18

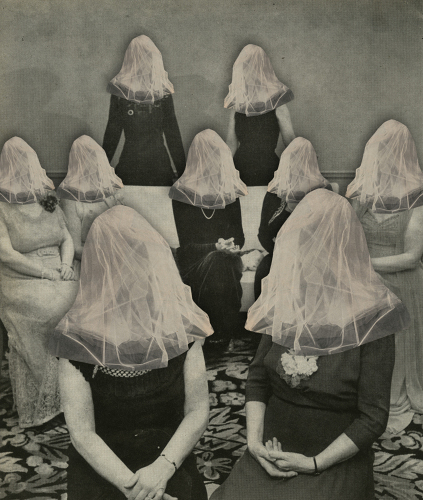

In another time, in another place, in the Road Warrior, we saw a vision of the future. Gatekeepers huddled against mutant hordes. The gatekeepers wore white, they all dressed the same, they valued the localized-community, concentrated wealth. They seemed nice. The mutants in black leather bondage gear frothed with rugged individualism, their inventive machines snarled idling on the dry valley floor. We’re there on the hilltop now looking down/back, from a different future, trying to suss out which side we’re supposed to be on.

At times we are overwhelmed by all these questions, all these unstable voices, unsure whether our reactions are retrograde or future positive. We are compelled to feel we have answers, conflicted over whether we are living in a moment of transcendent utopian revelation or an age hopelessly conservative and nostalgic. Fundamentally, it’s this binary rationalization that is so frustrating. And so, its with the music industry disrupted as harbinger of the new economy, we stare back into the mirror and return to music as a locus for listening into the mechanization of our environment.

“Listening to music is listening to all noise, realizing that its appropriation and control is a reflection of power, that it is essentially political.”

19

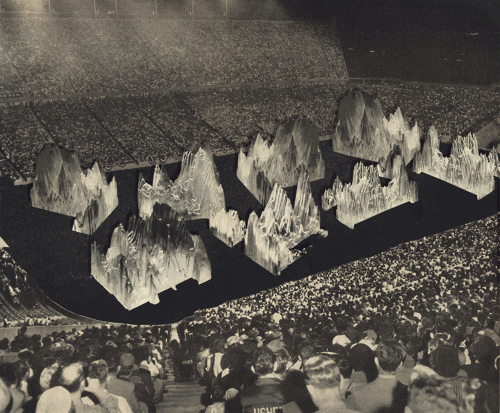

Music is our oldest language; it’s foundations largely spiritual, a network for allowing the community to resurrect the dreams of ancestors. Ritual music, the church hymnal, Yoruban Gelede etc. are communal appeasements to hold this fragile world together. “In that capacity [music] was an attribute of religious and political power [signifying] order, but also [prefiguring] subversion.”

20

Musical notation adapted this roll so that by the Enlightenment music was almost fully transformed from a means of awaking ghosts—looping into the past—into a method for conjuring the dreams of our future selves—the composer given primacy over divine orchestration.

Recording transformed this relationship further giving folk performance the same claim to both posterity and individual human autonomy. Suddenly freed from a telephone-game of unwritable history, the individual voice, the individual performance, the individual style was graphed and catapulted away from the local into ever expanding spheres of regional and temporal influence. The performance became more than the song, more than the notation. From the record to the jukebox to the radio to the South Bronx, these physical units of human experience claimed self-governance—their meaning both confirming the agency of the individual performer and recontextualizing it to fit the needs of future generations.

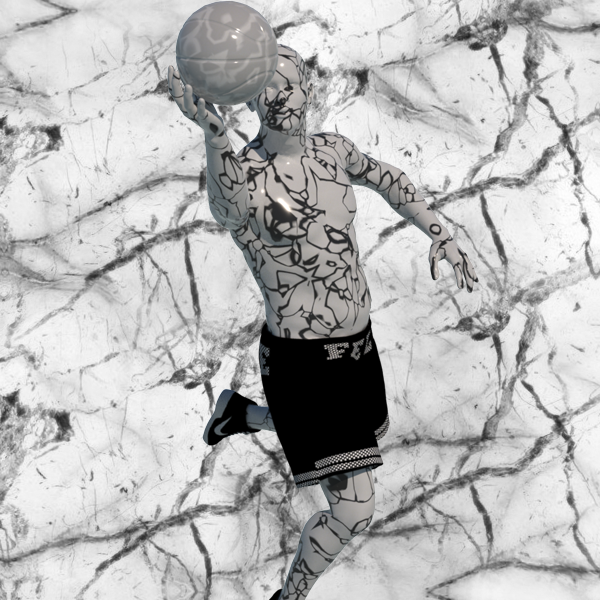

The rise of the independents gave auxiliary economic autonomy and tools to resist the pull to crystallize in the pop-center, even as it transformed that center. The expansion of the means for digital distribution and production now establish new forms, new exhibitions of agency, still not yet fully in focus and exasperatingly linked to old ideas of value controlled by consolidating capital-realist interests.

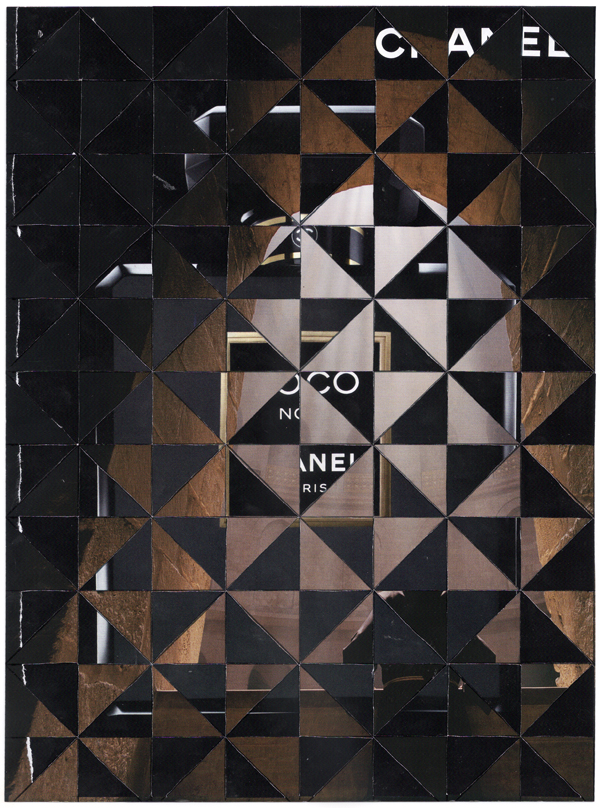

“Fetishised as a commodity, music is illustrative of the evolution of our entire society: deritualize a social form, repress an activity of the body,” the device, the cloud, the stream collapse the body to states of virtual dependence and infinite declarations of i-ness.

21 “Specialize its practice, sell it as spectacle, generalize its consumption, then see to it that it is stockpiled until it loses its meaning.”

22

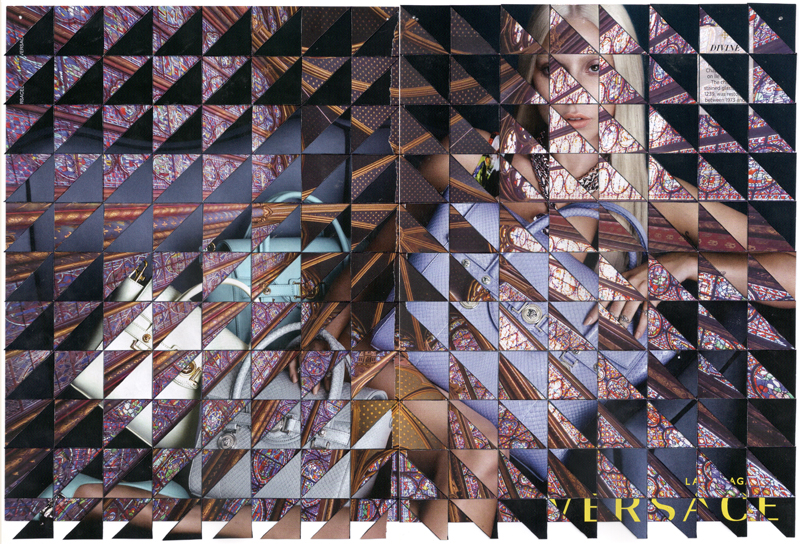

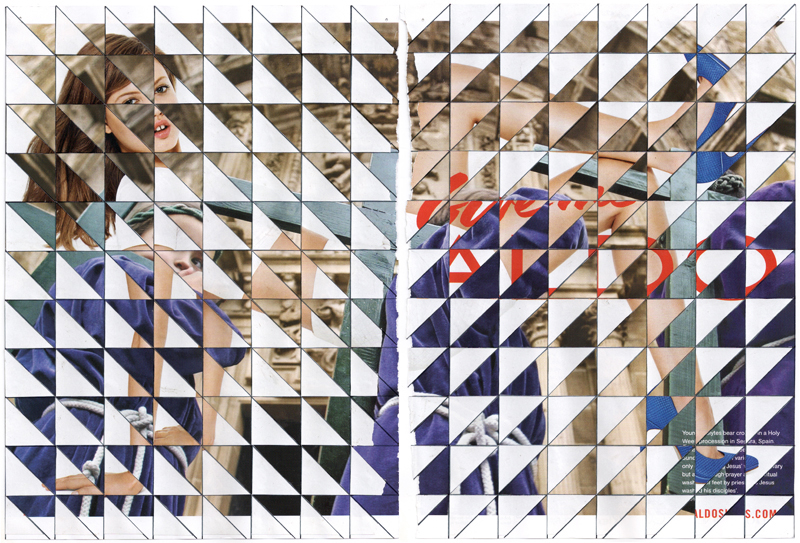

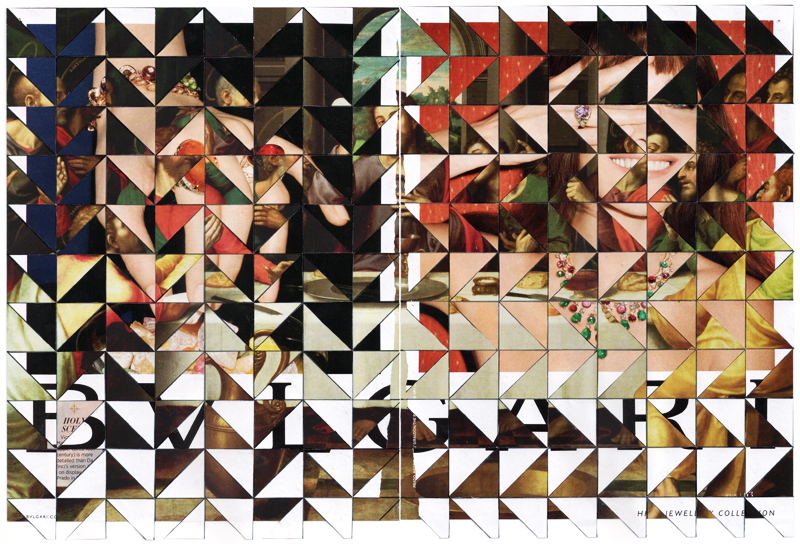

Music devalued through hyperinflation becomes everywhere and thus decorative. In this, cultural value is transformed from the individual unit of creation to the ancillary product of invisible value: the collection of meta-data to acquire portraits to divine the behavior of individuals.

“Eavesdropping, censorship, recording and surveillance are weapons of power.”

23

This we must remember remains true whether governments, corporations or individuals yield it and that censorship in the adaptation of algorithms to bury information in volume or by obscuring its discoverability, like Borges’ Library of Babel, is as potentially damaging as burning books. Super-evaporation into the cloud yields all culture vulnerable to these manipulations. As we build this system, we must think further into the future imagining how these systems might grow well beyond us and what power individuals not yet born might yield with it. This is the fundamental importance in prizing art objects that do not owe their existence to the network.

"The technology of listening in on, ordering, transmitting, and recording noise is at the heart of this apparatus… these are the dreams of political scientists and the fantasies of men in power: to listen, to memorize—this is the ability to interpret and control history, to manipulate the culture of a people, to channel its violence and hopes." 24

In practice, the dynamics at work shift back and forth from these schizoid positions largely forcing the conversation of new sounds under the scope of larger disconnected interests, most of which see little value in the autonomy of artists, or any need for art to have anything beyond decorative value. Lost in this bluster of industrial dynamics is the music itself, and the question of how to assess and support—financially and critically—new folk mutations, and how to differentiate between affectations of past experimentation and those avant-folk forms that evolve forward.

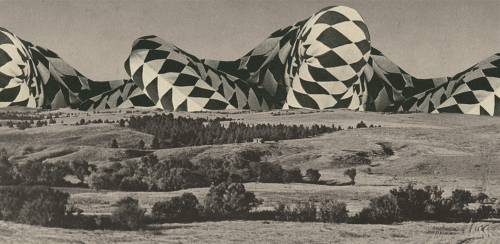

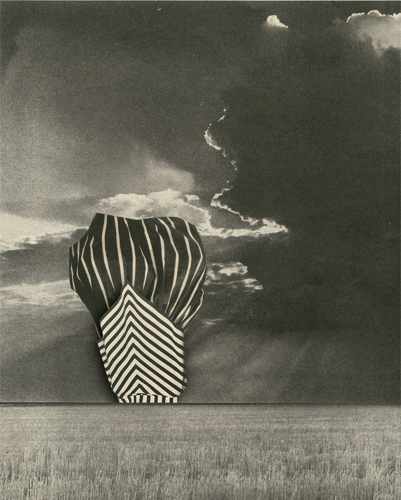

We need new processes to escape the trap of the zeitgeist to reclaim the future from the rush of immediate and compartmentalized reactions that keep us locked to the gluttonous, trending, now. In this we seek to return folk to a molten state, not a bucolic return, but out into the frontier where analogue, electronic, digital and acoustic mechanisms mutate with unexpected veracity.

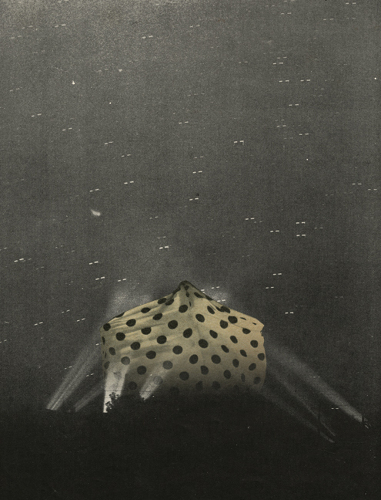

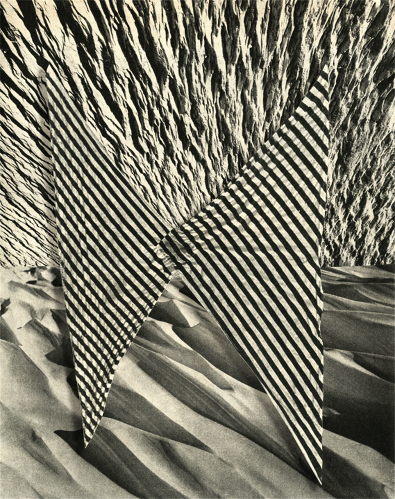

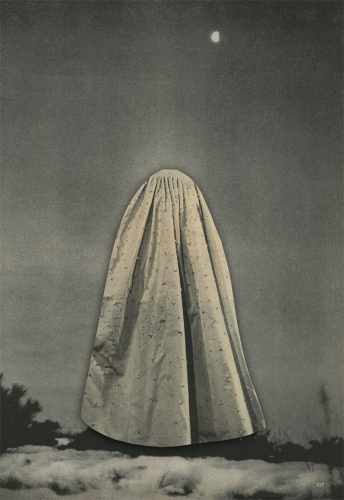

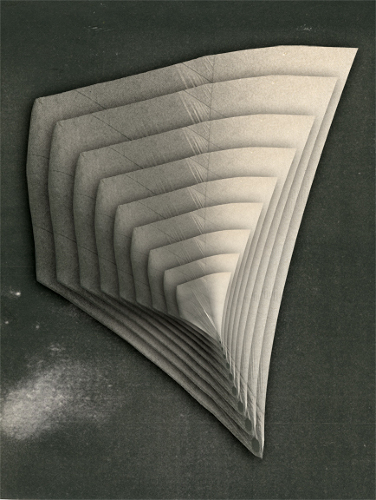

Digital production and the home studio yield new forms and textures, time-bent, heaving dynamics opening up spaces previously unimaginable. These vortexes of sound billow with the abstracted articulations of shredded digital realities. Shards of this are heard bubbling in the most forward leaning of avant-pop stylists who coil their voices into terrains that warble and blister. This becomes radically destabilized in the iterations of more esoteric works that demand patience and committed attention. Often these articulations exploit contradictions of commercial plasticity, encrypting subterranean folds into the deeper architecture of the format. At other times they are consciously removed from life in the box and the rigorous grids of digital space re-focusing attention to the primal and performed instrument, the acoustic terrain, the stretching and hypnogogic quality of tape, the architecture of lived environments and the poetics of space.

We are deliberately eschewing explicit examples; specific aesthetics and materials shouldn’t limit our scope. Too easily we devolve again to that binary logic, between sounds that are conservative (analogue, authentic, warm) and those that are new (founded in code, digital, cold). This is an artificial articulation of simulated velocity and sentimentality that misses the greater complexity of avant-folk trajectories that privilege the “idea of the new” or the “idea of the real” over truly forward leaning mutations. They are equally reactionary positions.

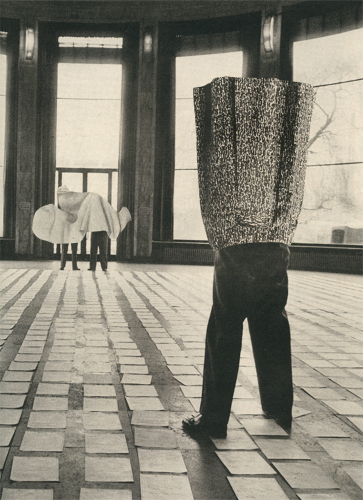

In the de-materialization of the sound object we are brought back closer to music’s first iteration. The DAW becomes the parlor piano, the parlor becomes the public space: music the province of localized acts linked to global networks. In this new ephemeral state, music can evolve to become purely transient—the background hum of advertisements and restaurants—or reclaim access to the metaphysical—a return into sacred space demanding presence and prescience.

In this the potential of the physical shouldn’t be forgotten, records are future fossils, they coalesce to preserve a history beyond the control of network and the zeitgeist. Objects that evolve with us etching our interaction, graphing each playing onto the tape or record have a future value, value we can’t predict but that must be thought of beyond units of consumption. We need newer dynamics and modes of thinking that push beyond the limitations of the MP3, the stream, two-channel mixing and the concert stage retand return us to the primacy of the sound object and event. In unlocking the potential of physical music, reconfiguring, formats to move beyond stereo 25 we can re-introduce scarcity in the object and space of music. Venues should become site specific engaging with the new realities of the laptop composer. These are critical mutations a generation of networked voices can seize upon and adapt so we can move away from the exploitive economies of interchangeable and endlessly reproducible content clouds.

More than a decade and a half ago, "adapt or die" was leveled as a charge against the complacency of the music industry.26 In this sense, the adapting principle is one of conforming to realities of commodity exchanges and for artists to become nothing more than conduits for aspirational consumption.

A true folk music must adapt to subvert these tendencies, to always challenge the status quo of the industrial economy, and it must self-organize to establish independent modes of financial support that privilege creation over consumption. This also means reassessing and questioning how we stream, how we consume and how we engage. We must undermine the mechanisms of the entertainment industry even as we pivot to ensure we fund truly independent channels of art production.27 We need more networks that act with love and generosity, creating ways to be self-sustaining and geared to artists uncomfortable in the zeitgeist, the hype-machine or with the need to become "entrepreneurial" hucksters. A network that doesn’t de-value the human contribution, financially or spiritually, that wrests control away from the limitations of corporate hive networks and venture capital backed ideas for digital busking. Adjusting the concept put forth by Jem Cohen and Astra Taylor,28 we propose: those who make vital culture, those who distribute it and those who receive it, must share a relationship of mutual protection and admiration: a triple anchor in which each end guards the other.